One of the hallmarks of all the terms I’ve surveyed so far is their positing of a certain kind of ideal entrepreneurial self, who possesses abundant moral strengths–“innovation,” “creativity,” “resilience.” At the same time, though, the rhetoric of austerity relies heavily on bodily metaphors for these supposedly innate values. “Flexibility,” for example, reframes the illogical fortunes of the economy as an athletic contest. While nimbleness, flexibility, and even “austerity” itself–as a moral reckoning with gluttonous excess–connote virtuous acts of self-discipline, branding’s origins in the painful marking of flesh have never totally left the word’s current usages. So…

Branding is one instrument of capital’s penetration of all spheres of everyday life, from schooling to health care to electoral politics. Its application to domestic consumer goods at the beginning of the 20th century marked its initial appearance in our vocabulary as something other than a mark of ownership on livestock. While branding has always been a mark of property ownership, the major transformation in the word’s usage from the 19th to the mid-20th century was the metaphorical “carrying over” of ownership from proprietor to consumer. In the 19th century, “brand” was most often encountered in verb form–typically to brand livestock–or as a noun formation from the verb, as in the “branding” of cattle. It is the direct, searing application of proof of ownership by the owner of land and chattel. The average consumer became the owner of branded objects between the late 19th century, when modern consumer branding makes it fitful start, and the middle of the 20th century, when in its heyday branded advertising focused primarily on domestic goods marketed to women. So “brands” become a designation of uniqueness, but this designation became less of a literal denotation of property and more of a symbolic connotation of quality. Hence the once-popular, and now quaint adjective “brand-name,” used to distinguish a product from the generic store variety. Branding was a metaphor that drew on the original mark of ownership, but the supermarket brand connected symbolic associations to everyday products–retaining the claim of ownership while losing the material referent of its first use, as hot iron on living flesh.

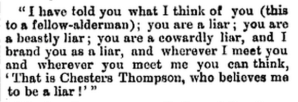

The verb’s metaphorical use in non-consumer applications was widespread in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but there it was widely negative. One of the most common usages of the verb then was in constructions like to “brand a coward” or “brand a liar.” So if branding today suggests thetranscendence of the debased materiality of the object–we can all easily recognize, for example, how Jiffy Peanut Butter represents not just peanuts ground into a delicious sweetened paste maternal love itself–its earlier figurative uses contained a similar moral meaning, something visible in, but transcendent of, the material reality of an object or a person. What’s been lost is the sense of humiliation that comes with being marked–exposed as a fraud, a sinner, or an object. Now, to brand a person, a non-profit institution, or an idea is, paradoxically, to elevate it, rather than debase it by comparing it to chattel, household cleaner, or peanut butter.

Take, for example, the concept of the “political brand.” An online course in political marketing at the University of Auckland in New Zealand (it is described as a “flexible learning” course) advertises itself with soup cans emblazoned with brand associations, a knowing if not particularly knowledgeable nod to Andy Warhol. “Whereas a product,” reads the course description, “has distinct functional parts such as a p olitician and policy, a brand is intangible and psychological. A political brand is the overarching feeling, impression, association or image the public has towards a politician, political organisation, or nation.” The phrase “political brand” goes back a long way, but until quite recently it was always used in the sense of “brand’s” mid-century consumer use–as a synonym for a “variety,” as in “Roosevelt’s Democratic brand of government.” Alternatively, in the Cold War, it was often used disparagingly, with the moral sense of the “brand” of dishonor: Tito’s or Castro’s “brand of Communism,” for example. Today, one typically hears it in the way the Auckland marketing professor means it: neither as a symbol of the product, nor a synonym for its distinctiveness, nor a mark of deceit, but as the political “product” itself. As far as I can tell from a search of the New York Times’ online archive, it is not until the 2004 election that “political brand” in this sense becomes common. Now, for example, the chair of the Congressional Black Caucus describes his disappointment with his Republican colleagues’ failure to observe the 50th anniversary of the Selma protests, he says that “the Republicans always talk about trying to change their brand and be more appealing to minority folks.” What’s strange about this that he doesn’t mean it cynically, as if a political “rebranding” of racist politics was an insincere gesture that conceals a basically reactionary heart. He’s sincere about the “Republican brand” as a meaningful expression of the Republican spirit. Martin Luther King’s “radical revolution of values” is now a rebranding.

olitician and policy, a brand is intangible and psychological. A political brand is the overarching feeling, impression, association or image the public has towards a politician, political organisation, or nation.” The phrase “political brand” goes back a long way, but until quite recently it was always used in the sense of “brand’s” mid-century consumer use–as a synonym for a “variety,” as in “Roosevelt’s Democratic brand of government.” Alternatively, in the Cold War, it was often used disparagingly, with the moral sense of the “brand” of dishonor: Tito’s or Castro’s “brand of Communism,” for example. Today, one typically hears it in the way the Auckland marketing professor means it: neither as a symbol of the product, nor a synonym for its distinctiveness, nor a mark of deceit, but as the political “product” itself. As far as I can tell from a search of the New York Times’ online archive, it is not until the 2004 election that “political brand” in this sense becomes common. Now, for example, the chair of the Congressional Black Caucus describes his disappointment with his Republican colleagues’ failure to observe the 50th anniversary of the Selma protests, he says that “the Republicans always talk about trying to change their brand and be more appealing to minority folks.” What’s strange about this that he doesn’t mean it cynically, as if a political “rebranding” of racist politics was an insincere gesture that conceals a basically reactionary heart. He’s sincere about the “Republican brand” as a meaningful expression of the Republican spirit. Martin Luther King’s “radical revolution of values” is now a rebranding.

The Personal Brand

Note the tense and aspect of the verb as it is conventionally used, as perpetually ongoing: either one “re-brands” or is in the act of “branding,” just as the Republicans in the example above are “trying to change their brand.” The past tense of the verb is rarely used. The verb thus manifests a curious, and painful, combination of searing permanence and constant reinvention.

“Personal branding” extends the logic of branding to the anxious professional class. The concept was popularized by the management consultant Tom Peters in his 1997 Fast Company article “The Brand Called You.” Peters is a master of the glib! conversational! exclamatory! prose that distinguishes this brand of self-help management literature!

Start right now: as of this moment you’re going to think of yourself differently! You’re not an “employee” of General Motors, you’re not a “staffer” at General Mills, you’re not a “worker” at General Electric or a “human resource” at General Dynamics (ooops, it’s gone!). Forget the Generals! You don’t “belong to” any company for life, and your chief affiliation isn’t to any particular “function.” You’re not defined by your job title and you’re not confined by your job description.

Starting today you are a brand.

Peters defines the personal brand as an exercise of what it might seem explicitly not to be: creative autonomy. Against the stability of the mid 20th-century tropes of executive selfhood–gray flannel suits, 35-year careers, gold watches upon retirement, etc.–Peters offers a reltentlessly upbeat vision. Branding at mid-century, Naomi Klein writes in No Logo, was “hawking product”; today it offers “corporate transcendence.” Peters, in turn, reminds you that you are not a product. You are a free-born, creative individual with limitless potential. You are, in other words, a brand.

Peters’ exhortations exemplify a kind of enthusiastic rhetoric about the so-called “new economy,” which advances what Brouillette characterizes as “a flexible, dynamic, self-regulating, entrepreneurial engine, willing to engage in constant reassessment and destruction of past beliefs and allegiances in pursuit of a more fulfilled and productive existence” (90). For the world of office workers this literature summons, stalked by redundancy and tempted by triumphs just within reach, the working day never ends, since branding yourself never should. And service workers, hidden behind their “branded” aprons and ballcaps, are more or less invisible.

Peters’ enthusiasm deflects the anxiety that undergirds the discourse of “personal branding.” As Dan Lair, Katie Sullivan, and George Cheney have argued in a recent article on the discourse of the “personal brand,” the “turbulence” of contemporary capitalist austerity is often misapprehended as a problem of communication: one’s failure to get along, especially in the “professional,” managerial, academic, and journalism worlds, is understood as a failure to acclimate to new technologies–the Internet in particular. The gurus of personal branding cultivate this sense of anxiety, because they are, of course, selling themselves as its solution. Communications media are treated as the cause of and solution to the unemployment crisis.

The “personal brand,” in short, is a concept that celebrates the self-commodification that Klein’s book denounced as the cruelty of corporate domination. It is framed as empowerment, an “investment in yourself,” and yet carries with it an unmistakable air of desperation. What’s notable, though, about many contemporary uses of “branding” is their indifference to the charge of inauthenticity. In Building Brand Authenticity: 7 Habits of Authentic Brands, its title an homage to one of the ur-texts of the executive self-help genre, Michael Beverland writes that “authentic brands” can obtain the qualities of “effective people.” Anticipating the objection, he writes, “Wait a minute. Isn’t the notion of ‘authentic brands’ contradictory?” This technique of engaging an audience with a just-folks rhetorical question, for which only 1 answer is permitted, is popular in these corporate genres, another example of the authoritarian fist barely disguised by the velvet glove of austerity-empowerment discourse.

The correct answer to this question is of course “No.” Brand managers, writes Beverland, “paint themselves as perpetual underdogs, fighting against the blandness produced by modern marketers.” (NB: when Beverland says that marketers “paint themselves” as underdogs, he doesn’t mean it as a criticism, like it sounds.) Instead, “marketers need to imbue their brands with a warts and all humanity and use the tools at their disposal to tell, and help others tell, stories.”

Critics of “personal branding” note that this surrender to self-commodification extends the reign of the corporate world to workers’ very sense of self, what we typically presume to be the source of “stories.” Indeed, its promoters are embarrassingly glib, their arguments superficial and easy refuted, and the packaging of their ideas stunningly inept for people whose expertise purports to be in self-promotion (for an example, see the Powerpoint slides–which I’ve edited merely for brevity–from one of Peter’s seminars). The self-satisfaction, the sloganeering, the relentless enthusiasm that seems to hide a profound spiritual aridity–all of these things that strike me as the incompetence of personal brand discourse are also part of its appeal.To borrow a similar point Brouillette makes in Literature and the Creative Economy about Richard Florida, the University of Toronto scholar famous for his tireless promotion of the “creative class” idea, branded ideas like personal branding, like the “creative class,” have an elegant, maddening coherence (22-24). All of their ideas about branding are brands themselves: digestible, imitable, and marketable, they are communicable in ways that cannot be easily disproven. In this way, branding’s underlying principles–the dynamic flexibility of the enterprising individual, the transcendent promise of the brand itself–are so thoroughly embedded in the professional, political, and educational institutions that have embraced “innovation” and “entrepreneurship” as core values–that is, brands.

Personal branding’s frank celebration of self-commodification reminds us of Weber’s reading of Benjamin Franklin’s utilitarian understanding of virtue. Virtues like honesty and modesty, Weber wrote in the Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, “are only virtues in so far as they are actually useful to the individual, and the surrogate of mere appearance is always sufficient when it accomplishes the end in view.”

Besides being an ethos, an act of faith in the market and a practice of disciplining oneself to meet its demands, “personal branding” is advertised as a necessary creative practice, in which solipsism and aesthetic imagination are scarcely distinguishable from one another. And while it aspires to transcendence, the brand’s familiar origins in the marking of property reminds us of the laboring body whose flexibility has psychic and physical limits.

[…] * Keywords for the Age of Austerity 17: Brand/Branding/Rebrand. […]

LikeLike

[…] Keywords for the Age of Austerity 17: Brand/Branding/Rebrand March 31, 2015 […]

LikeLike

[…] and managerial skills required of each.” He’s even more brutal when talking about Brand/Branding/Rebrand. Blog: Keywords for the Age of […]

LikeLike

I am looking forward to reading your book. However, apropos branding, while I agree with much of what you right, the origin of the migration of ‘branding’ from livestock to consumer goods, was when food retailing switched from loose to pre-packaged goods. There was a big tub or butter from which the grower would cut you a 1/4 lb or a tea chest from which the grocer would weigh you 1/2 lb or whatever. There was always a temptation of less scrupulous retailers to dilute a product or cut it with other stuff (like modern day drug dealers) or mix inferior quality tea into the chest etc. By pre-packaging a product, the food manufacturer was effectively guaranteeing that what was inside the packaging was the real thing, as it were. Branding then became the manufacturer’s claims for his product – 100% pure or only using the best quality teas etc. etc. That served a purpose, but nowadays ‘branding’ has gone crazy, even down to as you say, personal branding. As each individual is unique, even identical twins will differ in many ways due to upbringing and experiences, the idea of ‘branding’ yourself is lunacy as nobody is likely to mistake you for someone else, inferior, diluted or otherwise. Perhaps you have already included all the above in your book and I am definitely not trying to teach grandmother to suck eggs, but just a thought. In the meantime I look forward to the release of your book in January.

LikeLike

Great reading your poost

LikeLike