This keyword entry is an unusual one, since it doesn’t have the same business-world origins of most of our others. As a feature of post-1990s coverage of first-world political dissent, however, it fits our timeline.

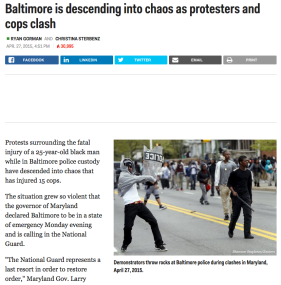

If you read any coverage of the Baltimore “riots,” you will read that formerly peaceful protests “descended into violence.” This cliché was inescapable in reporting on the Baltimore protests, as Sarah Jaffe observed on Twitter. It’s a standby of reporting on urban demonstrations in Charm City (a Baltimore Sun headline this week announced that protests “descended into chaos”) and around the world. Anti-austerity demonstrations “descend into violence,” the London Independent headline reported in 2011; after 8 Palestinians were shot dead at a Gaza demonstration in 1998, an Israeli defense minister told Toronto’s Globe and Mail in 1998 that he was “very concerned” that the Palestinians allowed things to “descend into violence.”

It’s a standby in war reporting, as well: The Economist reported, preposterously, that “fears are growing that Iraq may descend into violence as American troops leave” in December 2011, by which point many thousands had already perished during the Iraq War. In U.S. and UK media, it’s a phrase that links together all the violent trouble spots of recent world history in a sad fraternity: Afghanistan, Yugoslavia, Cambodia, Argentina, Northern Ireland, Mexico, East Timor, and South Africa have all “descended into violence” at some point. George Shultz, Ronald Reagan’s secretary of state, warned “black South Africans” to avoid an “easy descent into violence, terrorism and extremism” by seeking compromise with the apartheid government. If there is a place in the world that is already spectacularly violent, there is undoubtedly a reporter or official wringing his hands about its “descent into violence.”

As my colleagues Tracy Neumann and Quinn Slobodian have pointed out, “descents into violence” also frame retrospective accounts of 1960s activism in the United States and Europe. Here, the virtuous early 60s of non-violent protest and civil disobedience (the March on Washington did not “descend into violence,” noted CNN with approval) are distinguished from the “bad 60s” of rage and disorder (see the West German Baader-Meinhoff group’s “descent into violence”; when was this armed leftist organization anything but?) Finally, it comes up in the odd report on the murderous pathology of an individual criminal: “Killing of Cats Called Warning of Descent into Violence,” the Buffalo News reported in July 1998.

The phrase goes back in foreign policy reporting to at least the 1980s, but it’s typically been reserved for the “underdeveloped” world and its supposedly retrograde (hence “descent,” a movement backwards or beneath) predilection for disorder and revolt. The earliest use of the phrase that I could find to describe protest movements in the United States and western Europe is surprisingly recent: The Times of London ran a headline, “March against Le Pen Descends into Violence,” a report on a French march against the far-right politician Jean-Marie Le Pen, on March 31, 1997.

Perhaps the phrase comes into such prominence at the end of the 1990s because this is the beginning of an era of mass mobilizations in Europe and the United States (against globalization, neo-fascism as in the Le Pen case, austerity, and most recently, police killing).

From the days of our nation’s earliest civil rights sit-ins, Baltimore has a long tradition of peaceful and respectful demonstrations.

— Mayor Rawlings-Blake (@MayorSRB) April 26, 2015

Furthermore, these movements are shadowed, especially in the United States, by the sanitized myth of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the “respectful” civil rights movement that has become so dominant. Here, what King called “nonviolent direct action” becomes “peaceful protest,” which it decidedly wasn’t–if by “peace” we mean the public order and complacency that direct action is determined to upset.

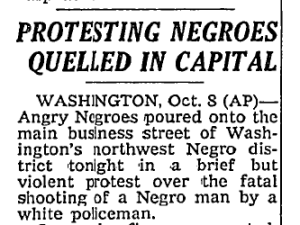

News coverage of riots and demonstrations from the 1960s is full of ominous warnings about “violence,” but there it is accepted as the expected order of militant protests, rather than a deviation from a respectable norm. A Feb. 9, 1964 New York Times article warning of rising racial tensions warned that “the carefully scrubbed, neatly dressed college students who sat down at lunch counters across the South in 1960 and politely ordered coffee are gone for the most part.” 4 years later, the Times ran this lede to a report buried deep on an inside page, so unexceptional was it in October 1968: “Angry Negroes poured into the main business street of Washington’s northwest Negro district tonight in a brief but violent protest over the fatal shooting of a Negro man by a white policeman.” Martin Luther King, Jr. was barely in the ground; his legacy of non-violent resistance hadn’t had time to be looted by the cynics today disguising their passivity by lamentations for “violence.”

“Descending into violence” thus rests on two words that cry out for explanation: what is “violence,” and if we’re descending into it, what are we descending from?

The imbecilic Wolf Blitzer was one of those who invoked King on CNN to demand that Deray McKesson, a prominent activist in Ferguson, repudiate the “violent” Baltimore protests. Put aside the obvious fact that if not for the “violence” he so deplores, Blitzer wouldn’t be talking about Baltimore in the first place. McKesson’s admirable, frustrated response derived from Blitzer’s inability to recognize the difference between the “violence” visited upon Freddie Gray’s spine and that dealt upon a store window. “Violence,” the Baltimore Sun’s headline suggests, is equivalent to “disorder,” “chaos,” and “looting”–anything that upsets the “peace” of the city’s normal business. Likewise, Blitzer seems to regard “violence” as, essentially, breaking anything; it matters not whether that thing is a body or a piece of property.

The Sun’s headline contained something revealing, meant to be excerpted for readers to share on Twitter: “Baltimore devolves into chaos, violence, looting.” This is where the use of the “descent into violence” for both third-world “troubles” and pathological murderers becomes relevant: the city Freddie Gray lived in had fully descended into “violence” once his spine broke. What makes what came after a “devolution” is the race of the protestors, and the pathological violence with which they are associated by a racist media.

And here, it is worth pointing out that of the words commonly used to delegitimize political uprisings, two–“loot” and “thug”–entered the English language via the British empire. “Thug” was an English slur for an Indian criminal, derived from the Hindi for “swindler”. As James Hevia writes in English Lessons: The Pedagogy of Imperialism in Nineteenth Century China, “loot” replaced earlier terms like “pillage” and “plunder,” evoking “a sense of the opportunities, particularly as ‘prize’ of war that empire building offered to the brave and daring.”

To loot, if you were an imperialist, was to bravely plunder; if you are one of the plundered, however, it marks you as a “thug,” already descended into unredeemable violence.

[…] * Keywords for the Age of Austerity 18: Descending into Violence. […]

LikeLike

[…] Keywords for the Age of Austerity 18: Descending into Violence May 1, 2015 […]

LikeLike

[…] phrases that push buttons, cliches that sound meaningful but in fact tell us nothing. The phrase “protests descended into violence,” for example, or some variation, is incredibly common. Protests in Baltimore, Ferguson and […]

LikeLike

[…] phrases that push buttons, cliches that sound meaningful but in fact tell us nothing. The phrase “protests descended into violence,” for example, or some variation, is incredibly common. Protests in Baltimore, Ferguson and […]

LikeLike