New from me at The New Republic: on the lamentations for this thing of ours.

New from me at The New Republic: on the lamentations for this thing of ours.

If you have been a Serious Political Commentator over the last four years or so, you have been worried and anxious and even unsettled about the rising tide of “illiberalism.” The word has always annoyed me because it sounds so pompous–something about the -il prefix, so rare in spoken English other than in the word “illiterate”–and is so non-descriptive. As a negation of an already poorly defined concept, illiberalism doesn’t communicate much of substance, but it does signal that one is a learned person with respect for “institutions” and a hard-earned knowledge that the world is complex. Like a lot of related hyperventilating about “free speech” on campus, much discussion about illiberalism focuses on surface-level stuff–tone, mode of address, style, things happening only online or in the media. Students yelling at someone they despise = illiberalism, students sitting at a table outside a hall where someone they despise is talking = liberalism. So, as a superficial concept used to telegraph depth, its currency tracks with Trump, not just because of his authoritarian desires or allegiances but because of the challenge, mostly rhetorical, to various sorts of “norms” and institutions.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, since the eighteenth century “liberal” has connoted “open-minded” and “tolerant,” a characteristic of an individual personality. This obviously informs its political uses, especially by self-described liberals: a liberal is someone appreciative of racial, ethnic, and religious diversity. Along these lines, we find that the liberal favors “social reform and a degree of state intervention in matters of economics and social justice,” a meaning that accords with the use of “liberal” in US politics. But the next political definition, “supporting or advocating individual rights, civil liberties, and political and social reform tending towards individual freedom or democracy with little state intervention,” complicates matters by invoking a parallel, and in some ways antagonistic, political tradition. This is what we might call the “libertarian” definition of the term. While sharing the concept’s basic orientation towards the individual as the basis of political life, their implications, especially in economic affairs, can be quite different.

But the designation “liberal” is really more a value judgment than a coherent political tradition. Its connotation of generosity (“princes are munificent, friends are generous, a patron liberal,” explains a nineteenth-century thesaurus) is used negatively in right-wing caricatures of the profligate liberal politician, but it is embraced by “bleeding-heart liberals.” Meanwhile, liberal in the sense of “unrestrained”—when we describe a libertine’s loose behavior or a trade agreement’s rules on capital movement—shadows the second, libertarian meaning, and lends itself to “classical liberal” or neoliberal. At the same time, liberal as “unrestrained” can be negatively repurposed as “undisciplined”—as in left- and right-wing mockery of the liberal as sentimental and soft-headed.

On the subject of soft-headed. All this imprecision is compounded by the fashionable adjective, “illiberal.” Whether one is describing campus radicals demonstrating too noisily against university policies, nationalist politicians mass-arresting their critics, left-wing politicians threatening to hold too many referendums, or people online being mean, “illiberal” is usually a useful pundit’s term for “that shit I don’t like.” The negative prefix, “il-,” calls to mind one of its definitions, “ill-bred,” an echo that, to my ear, heightens the anachronistic sound of the word and underscores the elitism its use covers for in the sorts of places (the Financial Times, The New York Review of Books, Foreign Affairs, the Atlantic, etc.) where one encounters it most often. But it’s not just my ear: derived from the Latin illiberalis, “sordid,” illiberalism’s snobbery is built into its etymology.

As I work through the new material for the new edition of Keywords, I’m going to occasionally post here some excerpts, outtakes, and other material that comes up.

Liberalism, writes Raymond Williams, is a “doctrine of possessive individualism.”

“Possessive individualism” was coined in 1964 by C.B. Macpherson, a Canadian socialist and political theorist who described it as a “unifying idea” of the political thought of the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries, during the long struggle for a more liberal state in England. To cut a long story short, he argues that human freedom came to be seen as self-possession: a free man was “the proprietor of his own person,” Macpherson put it (in more contemporary terms, this might be something like “your own boss”). This self-proprietorship is what makes us “free and human,” and politics is the medium by which individual proprietors peacefully regulate their claims with other self-proprietors.

Possessive individualism understands the freedom of the individual along the lines of the market—the freedom and humanity of a person depends on his freedom to pursue their own self interest through relations with others, and without dependence upon others. As Macpherson argues, this takes a relatively recent European contrivance—private property and ownership—and treats it as a natural, universal trait, the basis of what it is to be human. This is a conceptual problem that becomes a serious political crisis, he writes, in the twentieth century, as the rise of class societies and a working-class political movement throw into sharp relief the gap between metaphorical and literal “ownership.” If we are all proprietors of ourselves, in a class-stratified market society some people own more of themselves than others.

Which brings us to owning the libs, a metaphorical treatment of ownership of another as domination. In most contexts, this use of “own” is obviously ironic and even self-deprecating, without any trace of literal subjugation or anything: one declares oneself “owned” when you’re a good sport about another’s joke. But when used in earnest (as, incredibly, it still sometimes is) on the right, “own the libs” comes all the way back to the concept of possessive individualism. Here, as in “possessive individualism,” ownership is used figuratively, but it derives from a property relationship that is taken as a natural fact—that is, that there is something eternal and natural about the individual ownership of and trade in land, goods, and human labor as commodities.

Video game conventions, where the verb “to own” comes from, make an excellent example of this doctrine of individuality. Players typically play as discrete individual characters, who they customize in various ways as a surrogate self: a unique name, hair color, a set of skills, weapons, or other attributes. Even games in which users participate together still operate as a loose collection of individuals. (When I briefly ventured into online gaming, I was regularly berated by my supposed “teammates,” with whom I was ostensibly an equal but who were the proprietors of better endowed selves, an experience uncannily similar to everyday political life.) To own another player is to dominate them. If “man is free and human by virtue of his sole proprietorship of his own person,” and if political society is a contrivance to regulate the interaction of these proprietors, then the greatest political coup would be to disrupt the self-proprietorship of one’s enemies. They, who cannot properly own themselves, must therefore be owned.

An addendum to “protests descending into violence.”

By now, the world knows the name George Floyd. For this, we have the young people fighting with police in cities across the country to thank. But the deep and abiding love that pundits and TV hosts have for “peaceful protest,” which they profess as they narrate helicopter footage of riot cops in formation and burning police cars live from their studio, always misses this obvious point. Every riot and uprising in recent years gets the same treatment, at least on the media: “peaceful protests” “descended” into “violence.” In Baltimore five years ago, successful journalist impersonator Wolf Blitzer implored activists to stick to the script on respectable activism: “I just want to hear you say,” he nervously asked in one interview, “that there should be peaceful protests, not violent protests, in the tradition of Dr. Martin Luther King.”

As Mychal Denzel Smith wrote then at The Nation, this idyll of a “peaceful” King is ahistorical, not only for reducing the entirety of civil-rights history to one of its leaders but in its misapprehension of King’s tactics. He writes, “the civil-rights movement was not successful because the quiet dignity of nonviolent protests appealed to the morality of the white public.” Rather, Smith argues, nonviolent protest tactics provoked white violence, embarrassing political elites at home and the country at large abroad, in a Cold War context where the United States purported to lead the “free world.” Given how much these historical circumstances have changed, Smith rightly asked whether tactics should not evolve as well.

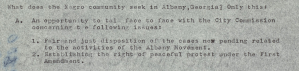

Beyond this important point, the common terminology is also wrong: given the frequency with which “peaceful protest” is invoked as a part of King and the movement’s legacy, you would think it had a history in civil rights activism. But King almost never said it. A quick search of The King Center archives turns up only one result for the phrase: the “Albany Movement Statement,” a document that laid out the position of the 1962 Albany, GA campaign, in which King lent support to local NAACP and SNCC leaders. One of the movement’s demands was “the establishment of the right of peaceful protest under the First Amendment.” (“Peaceful protest” also appears once in Taylor Branch’s well-known history of the Civil Rights movement, Parting the Waters, also in reference to the Albany campaign.)

On one of the rare occasions when King personally uttered the words “peaceful protest,” as in his 1962 speech to the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union District 65 in Monticello, NY–also in reference to Albany–he invokes it almost ironically, to show the depths of reaction in the Georgia town that was the site of King’s biggest defeat. The segregationists are so vicious they wouldn’t even allow that, he seems to say. “More than a thousand people have gone to jail,” he said of the Albany campaign, “merely because they want to be free, and engage in peaceful protest, in order to make that freedom possible.”

\In his own writings, King was much more likely to use the phrase “nonviolent direct action,” which was an expression of an evolving tactic–nonviolence exercised provocatively–rather than a character trait or moral state that must never change, like “peaceful.” Indeed, as Smith pointed out, “nonviolent demonstrations” were not at all peaceful, as he wrote in the introduction to 1963’s Why We Can’t Wait. On the 100th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, writes King,

freedom had a dull ring, a mocking emptiness when, in their time–in the short life spans of this boy and girl–buses had stopped rolling in Montgomery; sit-inners were jailed and beaten; freedom riders were brutalized and murdered; dogs’ fangs were bared in Birmingham; and in Brooklyn, New York, there were certain kinds of construction jobs for whites only.

“Peace” is a much more ambiguous word than “nonviolent,” whose grammar lays out its ground rules. Nonviolence is a tactic for unsettling the status quo; “peaceful,” the way the Joe Bidens and Wolf Blitzers use it, is the status quo. They use peace in the way that parents, police and other authority figures use it: “peace and quiet,” for example, or “disturbing the peace.” To the degree that talking heads think about it at all, they are thinking of “peace” as the quiet life that must not be upset.

On “moderate,” and the myth of a center lane:

https://newrepublic.com/article/157167/airy-ambivalence-moderate-politician-joe-biden

On “essential,” and the essential question: essential for whom?

https://newrepublic.com/article/157544/slippery-definition-essential-worker-coronavirus-pandemic

Just published in the New Republic and written in anger and disappointment on Wednesday, the day after Joe Biden won Michigan’s primary. In the days that followed, we’ve been treated to a round-the-clock advertisement for the urgency of Medicare for all and the dysfunction of a social and economic system built for endless competition and consumption.

Generational arguments usually seem suspect to me, predicated on some version of the cliche about young people having a heart and older people having a head, or else on some ahistorical faith in inevitable progress without political struggle–once all the backwards old people die off and the progressive youth take over, then things will really change. But it’s impossible to avoid the generational dynamics in this presidential race, and it’s equally hard to avoid being enraged by them.

“A return to the “normal” pace of the years before Trump has been Biden’s biggest pitch. But as The New Republic’s Kate Aronoff has pointed out, “there’s no normal to return to where the climate is concerned.” There is no resurrectable past. There is only a rapidly approaching future, which many of us have come to anticipate with a sense of dread. Many of those who voted, willingly or not, for Biden’s climate plan—which calls for carbon neutrality by 2050, decades too late—will never have to live with its consequences. Nor, of course, will Biden himself.

Our problem—the problem of people under 45 or so—is that we will live with these consequences. If you are obliged to think much further ahead than the next four years, it is impossible to be both honest and optimistic about the future.”

Most of what you ever wanted to know about Airbnb Magazine, in Jacobin: “I Read Airbnb Magazine So You Don’t Have To:”

“Because a lot of Airbnb’s workers are actually property owners, whether professional landlords or owners of real-estate portfolios, Airbnb labors very hard to do what comes more easily to services like Uber: putting a human face on twenty-first-century labor exploitation. On other sharing platforms, your interaction with the worker who powers it all is unavoidable. You are in your Uber driver’s car, after all, and you can chat with them; you might even enjoy their company. But alone in an Airbnb apartment, in an unfamiliar city, with only LIVE, LAUGH, LOVE posters for company, the fantasy of a real-estate subleasing firm that brings us together becomes harder to sustain. Into the aesthetic void of Airbnb steps Airbnb Magazine.”

An oldie but a goodie: I talked with Patrick Sheehan for the New Books Network about Keywords: check it out here.

New posts on terrible words may appear here from time to time, but for now, they’re in my new language column at The New Republic, called “Loose Talk.” Here they are, so far:

I was very excited to get to talk to some of the most excellent podcast hosts on the left recently: Katie Halper & Gabe Pacheco and Dan Denvir. Listen to my discussion with Katie and Gabe here:

And Dan Denvir, one of the best interviewers in the game, talked to me on The Dig. Listen here: