Check out “The Robustitude of Robust,” published today over at The Awl!

Author: John Patrick Leary

“Sold down the river”

I’m teaching Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson, a farce about biological definitions of race written in 1894, in the depths of the post-Reconstruction era. It is a comic genre story about slavery that mocks the racial definitions and distinctions upon which so many of American society’s other values–family, generosity, motherhood, “gentlemanliness,” the law, etc.–rested.

Its setting is a Mississippi River town in Missouri. At its core is a generic plot–two babies switched at birth. One of the children is the son of a light-skinned slave named Roxy and a local “FFV” (First Families of Virginia) gentleman, about whose “relationship” Twain pointedly and shamefacedly declines to elaborate. The other is the “white” son of a prominent local citizen, whose father is also Roxy’s owner. When the white boy’s father threatens to sell Roxy and her baby “down the river” to the cotton belt, she switches the two children in the cradle, making her own son her master and turning her young master into her child. The specter of what awaits “down the river” looms large in the imagination of the slaves in Dawson’s Landing, as a place of destruction and isolation. It looms as the greatest threat, and the cruelest punishment, with which a slavemaster can terrorize his property.

I asked my students if they knew the phrase, “sold down the river,” because I had always heard it growing up without any sense of the sale, or the river, in question. I remember thinking of it as one of those vaguely old-fashioned phrases whose origins you never wonder about–like “tickled pink” or “brownie points” or something. None of them said they knew it, which is in one sense a good thing. Yet Twain’s novel was a satire of his own murderous decade–the era of the KKK, of epidemic lynching, of Jim Crow’s consolidation–as much as, if not more than, the antebellum moment. The survival of the phrase indicates what a casual study of, say, the recent career of the Supreme Court might also confirm: that we are not far removed from the lynch mob and the poll test, though we like to pretend otherwise. That this history of violence and fear has lingered so long that it is still fresh on our tongues, but in the form of cliche that some of us never question and barely recognize.

Some others of “us,” of course, might know perfectly well what this phrase alludes to. But to confirm my own instincts, I searched the phrase on Twitter and found some surprising and not-so-surprising results. First of all, surprising: the phrase is apparently quite popular among British and Canadian political pundits, who use it to comment upon relatively “big” news issues like the Trans-Pacific Partnership and to complain about more banal inconveniences, like toll charges on a tunnel under the Mersey River.

Mersey Tunnel users ‘sold down the river’ on tolls according to campaign group – http://t.co/T8wVxt7nv5 #GoogleAlerts

— Drivers Union. (@DriverUnion) September 23, 2015

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

In 2 weeks, PM Harper goes down to defeat in fed. election. So I expect to be sold down the river in TPP trade pact talks.

— Andrew Goodman (@andrew_goodman) October 4, 2015

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

And note this pudd’nhead’s especially oblivious choice of words:

Ordinary folk have been cheated, stamped on and sold down the river by an elitist #system that would have you all believing black was white,

— Yvonne Anne Bolton (@frederickone) October 1, 2015

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

Less surprising, perhaps, is the phrase’s apparent popularity among Twitter right-wingers in the United States–the libertarians, conspiracy theorists, #TCOT nutters and bottom feeders that populate the medium.

We are about to be sold down the river by @SpeakerBoehner with @GOPLeader McCarthy RINO! #tcot @HouseGOP @RepDLamborn @GOP @Reince

— Liberty Bell (@libertybell1776) September 29, 2015

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

People with “benghazi” in their profile names are fond of it.

🔥MY REBUTTAL @SpeakerBoehner INTERVIEW ON ‘Meet The Depressed’ ☛SOLD 🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸 DOWN THE RIVER #PJNET #ORPUW #TCOT #TGDN pic.twitter.com/39RgVuR0GZ

— cmdorsey #BENGHAZI (@cmdorsey) September 28, 2015

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

@Badbadfox TOO LATE. AMERICA WAS SOLD DOWN THE RIVER BY DEMOCRATS/LIBERALS & GREEDY SKUNKS WHO PUT MONEY & POWER BEFORE PATRIOTISM!

— VoiceAmericanPatriot (@BizNetSC) September 30, 2015

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

It’s also quite popular among far-right UKIP partisans, an ideologically fitting but historically somewhat puzzling phenomenon–given that they are racists without, I’m assuming, a conscious knowledge of the phrase.

@5and20to5 Yes true only for our politicians to sell our country down the river. pic.twitter.com/owaDbJm4mp

— William Southall (@5970b43f3bd14f2) September 17, 2015

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

@rog_ukip They have no matter between the ears to see what is happening to this Great Nation of ours sold down the river at any cost.

— Herbie Crossman (@HerbieHarrow) October 4, 2015

//platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

And finally, white supremacists whose states’ rights have been “sold down the river,” showing once again the old cliche about the past never being past.

@PhxKen I doubt she had a choice anymore. @kygov sold their states’ rights to the devil & their people down the river! As have all states!

— Tennessee Militia (@SaveOurSouUls) September 14, 2015

KFTAOA mailbag: “take ownership”

A reader suggests the execrable verb phrase, “to take ownership”; eg, “Students will take ownership of their learning by creating learning portfolios.”

Thanks for reading, Scott!

At the next Republican presidential debate, consider playing the Keywords for the Age of Austerity drinking game. See how much fun you could have with Scott Walker, from his loony new policy brief on breaking unions nation-wide:

“Freedom and opportunity enable employees and employers to be creative, flexible, and innovative in the workplace.”

Keywords for the Age of Austerity 22: Collaboration (part 2 of 2)

“Keywords for the Age of Austerity” is a series on the vocabulary of inequality. Certain words, as Raymond Williams wrote in his 1976 classic Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, bind together ways of seeing culture and society. These shared meanings change over time, shaping and reflecting the society in which they are made. Some of the words I will consider here are old, seemingly innocent terms that have acquired a particular fashion or developed a particular new meaning in recent years; others are recent coinages. All of them relate to affinity for hierarchy and a celebration of the virtues of competition, “the marketplace,” and the virtual technologies of our time. This series will explore the historical meanings embedded in these words as well as the new meanings that our age has given them. This week’s post continues my collaboration with Bruno Diaz on “collaboration.”

Collaboration

1) “United labour, cooperation; esp. in literary, artistic, or scientific work.”

2) “traitorous cooperation with the enemy”

Last week’s post on “collaboration” showed how its primary associations with cooperative, especially intellectual labor–artistic, scientific, or otherwise–have been captured for use in the hierarchical modern workplace, from the “teams” of the service sector to the “pods” and “labs” of the white-collar office. Like “flexibility,” and the (forthcoming) “creativity,” it’s an ageless concept with little of the air of novelty linked to entrepreneurship and innovation. The perseverance and reinvention of such timeless concepts are one reminder, of course, that we are indeed living in the most innovative of all possible worlds.

As Bruno Diaz explained last week, “collaboration” is used to refer to any co-operative effort at work, especially across lines of seniority or rank, since the ostensible purpose of collaboration is to flatten hierarchy. Hence, in medical settings, the interest in nurse-physician “collaboration” and, in private business, framing meetings with subordinates as collaborative “coaching” sessions. It is also, of course, a labor-saving device: factory automation, by which human workers are made redundant by mechanical substitutes, has been rebranded as “human-robot collaboration.” This MIT Technology Review headline almost parodies itself with its blithe cheering of our new robot overlords: “Robots are starting to collaborate with human workers in factories, offering greater efficiency and flexibility.”

Collaboration has two meanings, though, both synonymous with “cooperation”: the second, political meaning refers to traitorous cooperation with an enemy. The word’s two meanings–the sunnier shared labor that social media and a flexible economy gives us, with its egalitarian suggestion of mutual aid, and the act of traitorous “collaboration”–seem at odds, as no less an authority than Thomas Friedman has already observed.

Friedman spun this 2013 homily on Silicon Valley “collaboration” as a model to be adopted by Friedman’s version of Washington, where “partisanship” rules and the only “collaboration” is the bad, traitorous kind. Since all of his columns are more or less the same, we need not get in too deep here: Friedman’s routine category confusions, his glib oversimplifications, his pompous and lazy reliance on anecdote, and his power-worship are all on fine display here. Friedman does not want you to think he is some silly polyanna, though. Collaborative though it is, “Silicon Valley is not some knitting circle where everyone happily shares their best ideas.” No, it is instead a place of non-stop manly clashing:

Friedman spun this 2013 homily on Silicon Valley “collaboration” as a model to be adopted by Friedman’s version of Washington, where “partisanship” rules and the only “collaboration” is the bad, traitorous kind. Since all of his columns are more or less the same, we need not get in too deep here: Friedman’s routine category confusions, his glib oversimplifications, his pompous and lazy reliance on anecdote, and his power-worship are all on fine display here. Friedman does not want you to think he is some silly polyanna, though. Collaborative though it is, “Silicon Valley is not some knitting circle where everyone happily shares their best ideas.” No, it is instead a place of non-stop manly clashing:

the most competitive, dog-eat-dog, I-will-sue-you-if-you-even-think-about-infringing-my-patents innovation hub in the world. In that sense, it is, as politics is and should always be, a clash of ideas. What Silicon Valley is not, though, is only a clash of ideas.

Only that is what Silicon Valley is, therefore, not. It is, instead, also different–collaborative. Understand? Head over to Richard Branson’s blog, where any lingering doubts about what he calls “the wonders of collaboration,” and the reasons that we are now living in the golden age of it, will only be compounded by his use of the term to encompass every philanthropic virtue. Branson comes closest to making a point (not a good one, but still) when he echoes Friedman’s use of the tech industry–at least its most user-friendly and well-known product, social media–as an example of what “collaboration” portends:

The beauty of the rise of social media is that power has shifted from the hands of small, centralised groups to millions of people around the world, who can make history at the click of a button, on a moment’s notice.

Collaboration’s traitorous meaning is not used explicitly by these new apostles of “social” capitalism, but it looms in the background, as the centralized, divisive, partisan, and old-fashioned foil to the decentralized, horizontal, efficient, and creative economy of our “innovative” fantasies.

Keywords for the Age of Austerity 22: Collaboration (1 of 2)

Editor’s note: this post is a collaboration. After all, to truly understand the cannibalization of a once-innocuous concept like “collaboration,” one has to experience it first-hand, to step inside its proverbial bloody, desiccated skin and walk around for a bit. So I asked UK marketing consultant Bruno Diaz to help chart the use and abuse of “collaboration” in what he calls the “digital workhouses” of the modern office. Together, we will wade into the goo-filled paddling pool that is the Keywords for the Age of Austerity 22: Collaboration. That is, just as soon as he gets me my coffee.

Continue reading “Keywords for the Age of Austerity 22: Collaboration (1 of 2)”

From the KFTAOA mailbag

A reader writes: “‘ROBUST’…..Personally I regard this as the single most dickish word in current circulation. Please have at it. Thank you.”

Have no fear, reader, it is in the queue and slated for destruction in the next month or so.

Arne Duncan comes down with a case of acute Keyword logorrhea, reports Inside Higher Ed

“White House pivots to accountability and outcomes,” reads the distressing headline on Arne Duncan’s call “for colleges to be held more accountable for graduating students with high-quality degrees that lead to good jobs.”

Misdiagnosing the disease and misprescribing the cure, Duncan’s “pivot” is a classic example of the deceitful rhetorical misdirection implicit in that word. You “pivot” when you want to change the subject or avoid uncomfortable conversations, as Duncan does here in “seeking to reframe higher education discussions around student outcomes rather than student debt.” This is a response, the article suggests, to pressure from student groups (like the Corinthian debt strikers) and presidential candidates, which presumably means Bernie Sanders. Duncan “pivots” to “accountability” and market-driven “outcomes,” and away from the less market-friendly problem of tuition and debt.

So: less debt relief for students, more bureaucratic oversight and expense for faculty, more economic pressure on students.

Keywords for the Age of Austerity 21 / Wednesday Night Fights: “Equity” vs. “equality”

Tonight we debut an occasional, perhaps never-to-be-repeated feature called “Wednesday Night Fights,” in which two similar terms go head-to-head to reveal which one is the true Keyword for the Age of Austerity. Two words enter, only one leaves.

Suggest potential candidates here or here.

On Twitter the other day, my friend @ughitsaaron suggested “equity” as a potential Keyword. As he points out, it is often used as a synonym for “equality,” but seems to really mean “fairness,” a more limited definition. One example of this usage comes up in a Guardian article about whiteness and activism in the Black Lives Matter movement: “we need co-conspirators, not allies,” said one activist, demanding the disciplined, intentional movement-building solidarity of “conspiracy” instead of the atomized, individualistic, even narcissistic position of “allyship.” Journalist Rose Hackman quotes one African American speaker at a demonstration who tells a crowd that whites in solidarity with the movement must “work to make sure that black people are given the equity that we deserve.” Or take this example from the Washington Post, on the campaign to extend D.C.’s mass transit into parts of Prince George’s County, a historically Black suburb, that are poorly served by the Metro. The proposed Purple line, the journalists write, would be an “instrument of economic and social equity.”

I don’t actually contest the point being made in either case, and the words are so similar that it’s understandable that writers and especially speakers might use them interchangeably. But why the turn to “equity” when the seemingly more familiar and, to my ear, more sonorous “equality”–the “equal chance and right to seek success in one’s chosen sphere regardless of social factors such as class, race, religion, and sex”–is clearly the intended meaning?

When “equity” is used in this political sense, it is (in the United States, anyway) used most often in close proximity to the adjectives “racial” and “educational” (or both). See, for example, the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity, or the Aspen Institute’s roundtable for racial equity (its function: “to think, talk and problem-solve around race”). My own institution, Wayne State University, features a project run through its Law School’s Keith Center for Civil Rights called the Detroit Equity Action Lab, whose purpose is to “address issues of structural racism in Detroit.” One of its biggest funders, the Kellogg Foundation, notes on its website that that “racial healing and racial equity are essential if we are going to accomplish our mission to support children, families and communities in creating and strengthening the conditions in which vulnerable children succeed.” The Portland, OR Public Schools calls its initiative on the “achievement gap” between white students and students of color its “Racial Educational Equity Policy.” And the U.S. Department of Education headlines one of its major policy statements “Equity in Education” (in which the one use of “equality” seems merely stylistic, to avoid repeating “equity” twice in one sentence). Perhaps the use of “equity” to describe racial and educational inequality reflects the fact that in the United States, “inequality” in general is often understood as a function of race alone, and public schools have been a primary (some might say the primary) way of addressing racial segregation. But the fact that so many institutions prefer racial equity to racial equality suggests that “equity” is a more neutral, more anodyne, less demanding alternative to “equality,” and less likely to tempt political opposition. After all, no one can be against “fairness.”

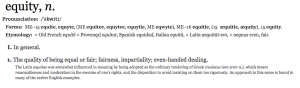

“Equity” is most often used in its financial sense: “the difference between the value of the assets and the cost of the liabilities of something owned,” Wikipedia tells me. It does, however, have a social meaning as well, whose OED definition is at left . Equity is a disposition, here–the “quality of being equal,” or “even-handed dealing.” It’s an individual characteristic or behavior, rather than a social or political condition. The distinction becomes even sharper when we consider the Greek etymology the dictionary gives us (admittedly, it’s buried deep in the word’s history, as the source for the Latin equitas). ἐπιείκεια, says the OED,

. Equity is a disposition, here–the “quality of being equal,” or “even-handed dealing.” It’s an individual characteristic or behavior, rather than a social or political condition. The distinction becomes even sharper when we consider the Greek etymology the dictionary gives us (admittedly, it’s buried deep in the word’s history, as the source for the Latin equitas). ἐπιείκεια, says the OED,

meant reasonableness and moderation in the exercise of one’s rights, and the disposition to avoid insisting on them too rigorously. An approach to this sense is found in many of the earlier English examples.

Equity, then, was both an individual characteristic–a characteristic or behavior–and a kind of moderate, inoffensive disposition towards fair dealing. Note again the second half of that first sentence: “the disposition to avoid insisting on [one’s rights] too easily.” So: less allies, more co-conspirators; less equity, more equality?

Winner and newest Keyword for the Age of Austerity: Equity, in a landslide.

More on “innovation,” in Salon

My essay on the prophetic meaning of “innovation” rhetoric–which Salon ran under the rather overwrought headline “Innovators are Killing Us”–is up now!