In its editorial on Evo Morales’ re-election victory in Bolivia last week, the New York Times described Morales as one of a group of “new caudillos” threatening “democratic values,” united in their desire to “appoint allies to electoral and judicial bodies and to build patronage networks that turn out the vote,” “weaken institutions,” and assert “greater control over the press.” (Note the evasive comparative adjective in this last—greater than what?). Glenn Greenwald has already observed how “democracy” here is little more than a code word for U.S. power. “Meanwhile,” Greenwald concludes, quoting the editorial, “the very popular, democratically elected leader of Bolivia is a grave menace to democratic values – because he’s ‘dismal for Washington’s influence in the region.’”

Any hand-wringing about “democracy” in Latin America should of course remind readers of Latin America’s Cold War, when the most horrific mass cruelties were justified in its name. And “caudillo’s” popularity shows the durability of Cold War terminology. It’s always used in English media to signal to an audience the author’s historical seriousness and command of the subject (“Well, in Latin America, you see, they have a term, ‘caudillo,’—you know, it’s pronounced COW-DEE-YO”]. The Times’ editorial is a textbook example of this usage. At its best, the word is simply a pretentious misreading of Latin American history, and at its worst, an ethnic slur. Yet there is something strange about the persistence of the word “caudillo,” if only because it belongs to both the Spanish language and to history, and U.S. journalism is so often incurious about both.

The Spanish Fascist Francisco Franco, whose rule coincided with the term’s revival in English media in the 1930s, was “El Caudillo,” the caudillo to end all caudillos. A casual search of the Times’ archives shows how“caudillo” is always used in either a lapsarian or apocalyptic sense. Last week’s editorial was not the first to ward off, fingers crossed, the rise of the “new caudillo”; one reads always of the “last caudillo” or the “return” of the caudillo. Debates raged about who was the “worst caudillo” ever in the Dominican Republic. Michele Bachelet of Chile, who is a woman and therefore not a caudillo, took power, naturally, “after the caudillo.”

Woody Allen as a bearded caudillo in Bananas!

The term “caudillo” is by now so saturated with Anglo-American stereotypes of the Latin American macho that it is useless as a meaningful term to describe anything except typical U.S. misconceptions of Latin America. Often translated as “strongman,” the origins of the political form of caudillismo are in the tumultuous post-Independence period in South America, where regional political or paramilitary bosses asserted control over provincial territory in a weakened central state. For this reason, continuing to call Evo Morales or Nicolas Maduro “caudillos” seems like the equivalent of calling Barack Obama a “robber baron” when he bypasses Congress. In other words, even if there is a grain of truth in the analogy, the popularity of “caudillo” shows how when discussing Latin American politics the recourse to tropes of “backwardness” is nearly irresistible. A U.S. president’s faults are of his own time; on the other hand, Latin Americans are always battling back the primitive past that lives in their midst and in their heads.

The New York Times’ reference to Bolivia’s allegedly degrading “democratic values” is a clue to the term’s basically culturalist meaning. For all the editorial’s lawyerly talk of “institutions” what we’re really talking about here is an authoritarian cultural predisposition, native to the soil south of the Rio Grande. Why else use the Spanish word to describe what is essentially party politics everywhere else? The term “caudillo” suggests that this is a political form peculiar to Spanish America, but by their own definition, the New York Times could use it for any head of a political machine anywhere. Is Michael Bloomberg, who revoked the city’s term limits to serve three terms, New York’s “last caudillo”?

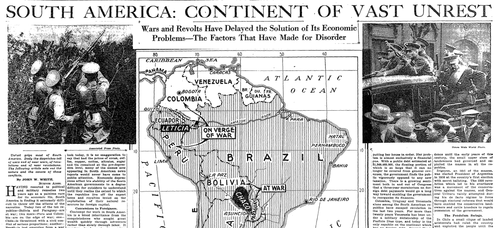

The New York Times, October 9, 1932

Note that this doesn’t foreclose Latin Americans and Latin Americanist scholars from using the term. For example, see the anti-Chavez Venezuelan political scientist Javier Corrales’ coinage of the term neocaudillismo (note, again, how caudillismo is always renewing itself). Corrales shows the difficulties of trying to forge a coherent political theory out of what is essentially an ethnic stereotype. In his estimation, neocaudillismo includes both newcomers and political outsiders (like Evo Morales and Hugo Chávez in Bolivia) and ex-presidents returning to office (Alán García in Peru and Carlos Menem in Argentina), so one wonders who it excludes. “Latin America is still the land of caudillos,” Corrales concludes, in a sentence that sounds like it was written a half-century ago. “These new caudillos may not promote coups, insurrections, or totalitarianism, but they still weaken parties, erode checks and balances, and scare adversaries.”

The popularity of “caudillo” signals the obsession with “political institutions” in foreign policy and development literature as the meaningful instrument and measure of progress. And progress, of course, has usually meant imitation of the United States, where “political institutions” are of course strong, fair, and non-partisan, except when they aren’t. And this is why, for me, there is this odd tone of familiarity with the caudillo in the U.S. press and academia—I can’t think of an equivalent “insider” term in foreign-policy coverage of other parts of the “third world.” Saudi Arabia and Cambodia, say, are so unfamiliar that they must be translated. But we know Latin America, the term seems to suggest, and we how it could be so much more like the United States, if only it could vanquish the partisan caudillos who are always reappearing, have just reappeared, or have just been vanquished, only to reappear again—one more instance of what Martí called “the scorn of our formidable neighbor who does not know us.”

.