A New York Times op-ed written by Jayne Merkel, an architecture critic, argues that the New York City Housing Authority could address its vast backlog of unfinished repairs—caused by the long-term cuts in federal funding—by training residents to make their own repairs. She calls this “A DIY Fix for Public Housing.”

The argument rests on a couple of obvious major fallacies. As with so many of our keywords, it values individual derring-do and ignores structural forces, resulting in the apolitical assumption that closing the federal funding gap is impossible, and thus “arguing over who will make nonexistent repairs is fruitless.” (One could borrow this logic to dismiss any political demand that seems, as most important ones do, unrealistic: “arguing about how women will exercise their nonexistent franchise is fruitless,” “arguing about taxation with nonexistent representation is fruitless,” and so on.). Second is its confidence that “almost anyone can replaster a wall.” (No.)

Reader Barbara A. Knecht of New York City already pointed out the idea’s other problems, in a letter to the editor so sensible one wonders how it slipped by the editors:

…[F]or the cost and time to develop, administer and insure a training program, the authority could employ and deploy the trainers to make repairs.

…Would the same recommendation hold for the residents of a Park Avenue rental building with a noncompliant landlord? Housing authority tenants pay rent and have a right to expect their landlords to keep up their end of the contract.

Knecht points out something both very old in the history of “do-it-yourself,” and something very new in its recent appropriation as a term of austerity individualism. Informal and inexpert by nature, straddling work and leisure, DIY has never been a strict necessity: you don’t just “do it yourself” because you have to, but also, and sometimes mostly, because you want to. This informality obviously makes it a poor solution for an affordable housing crisis.

Popular Mechanics, Jul. 1960.

What seems new in Merkel’s use of DIY is the migration of this individual ethic of “do-it-yourself” to the sphere of social policy. Besides improving the plaster and the work ethic of public housing residents, a DIY spirit will also relieve the state of its obligations to them. And so, like its close cousins “local,” “artisanal,” and the neologisms “hacker” and “maker,” DIY is a practice of middle-class consumption masquerading as a practice of citizenship. And like the cult of entrepreneurship, such uses of “DIY” reframe social disempowerment as individual achievement, delegating to citizens social costs without giving them any social power in return. It is a lamentable sign of our times that 1) someone can seriously propose that public housing residents, mostly people of color, should work without pay for their landlord and that 2) such a proposal pretends to be “progressive.”

As Steven Gelber has argued, the rise of “do-it-yourself” as amateur home repair dates to the middle of the 20th century. By 1950, the classified section of Popular Mechanics advertised an array of tools and tutorials to do-it-yourselfers.More Americans lived in owner-occupied homes than ever before—30 million by 1960, 10 times the number in 1890—and a majority worked for someone else. The growth of home ownership and the separation of home and work space created the conditions for doing it yourself as a middle-class, mostly male pursuit.

From Popular Mechanics, Mar. 1960: do-it-yourself leathercraft, welding, laminating, and…will-writing.

“When industrialization separated living and working spaces,” Gelber writes, “it also separated men and women into non-overlapping spheres of competence.” But the desire to do-it-yourself came not just from economic necessity, argues Gelber. It was a satisfying hobby for desk-bound workers and a respectable way for men to share the labor of the home while asserting a degree of autonomy and expertise within it. Even as the exclusively male claim on “do-it-yourself” culture has frayed, any Home Depot commercial or Tim Allen rerun will remind us of the anxious performance of masculinity that comes with doing it yourself.

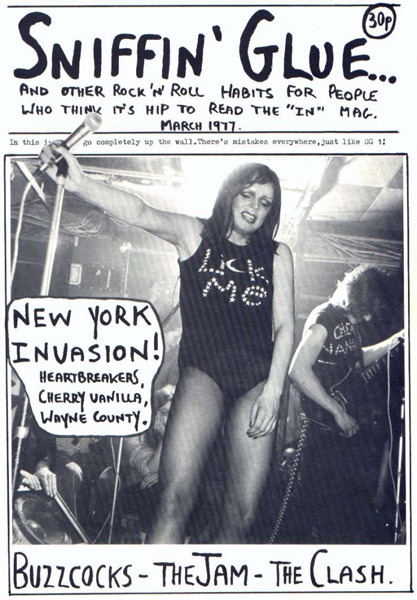

It’s not clear (to me) when DIY regularly appeared as an acronym, but many contemporary uses of the word draw on its association with the print style of self-published punk fanzines and the anti-professionalism of punk more generally. Historians of punk often credit the short-lived 1976-77 London zine Sniffin’ Glue with popularizing the DIY aesthetic—a graphic language built on Xeroxed pages and hand-written or cut-and-pasted type, and a writing style celebrating the close, collaborative networks of authors, bands, and artists.

As Sniffin’ Glue’s creator Mark P. insisted, however, the impulse towards self-producing streamlined industrial products—whether they are music magazines or manufactured goods—goes back further, to other forms of sports and music zines in Britain and to countercultural publications like the 1960s publication Whole Earth Catalog, subtitled “Access to Tools.”

In a recent essay in The New Yorker, Evgeny Morozov makes an insightful critique of the contemporary celebration of “makers” and “hackers,” which borrows rhetorically from the rebellious posture and community-mindedness of punk DIY. He traces it further back, to Whole Earth and to the turn-of-the-century Arts and Crafts movement. (To me, punk DIY, as a specifically media movement, seems different, since punk zines never pretended to be reforming the industrial labor system, and therefore had less of the apolitical hubris that for Morozov fatally compromise the Arts and Crafts and 60s “maker” movements). Arts and Crafts, as Jackson Lears has also written, responded to regimentation and inequality in modern industry by reviving old methods of craft production. By restoring to the worker the autonomy the factory had taken away, the movement would also provide consumers with the beauty they were missing. Yet without structural reforms of the economic system, critics pointed out, Arts and Crafts, which aimed to liberate workers, just became a niche market for middle class consumers. Morozov levels the same charge at so-called “makers” today, who see “ingrained traits of technology where others might see a cascade of decisions made by businessmen and policymakers.”

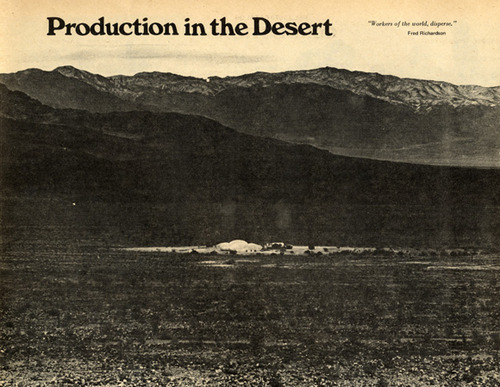

“Workers of the world, disperse.”

Supplement to the Whole Earth Catalog, January 1971 (via moma.org)

Morozov quotes one of the maker movement’s apostles, Kevin Kelly, who writes in his book, Cool Tools: “The skills for this accelerated era lean toward the agile and decentralized.” This technophilic rhetoric of speed, nimbleness, and decentralization in the individual parallel the celebration in the corporate world of the same values for capital. As in Merkel’s DIY fix for public housing, which imagines the collective of public housing residents as an assemblage of atomized, vulnerable “yourselves,” the DIY celebration of autonomy can be easily colonized by a corporate zeal for individualism. (To make the link with government austerity even clearer, Merkel ends her column by saying that public-housing residents could “take pride in his or her home…and save the city millions.”)

And now, search Twitter for “DIY” and you will find a host of consumer goods which offer evidence of this: the so-called “sharing economy” has appropriated the DIY label, reframing the vulnerability of precarious employment as self-fulfilling autonomy. Etsy craftmakers eking out extra income hustling “DIY” crafts online, AirBnB apartments are DIY hotels (or, more grandiosely, “DIY urbanism”), and Uber asks you to do cabdriving yourself, with little regulation and decreasing pay.

If, as some have argued, the abuses of the “sharing economy” fall hardest on women and in female-identified professions, then it is no surprise that “DIY,” once the male preserve of Popular Mechanics and This Old House reruns, now markets itself mostly to women. And of course, we should applaud fewer Tim Allens, fewer macho tool commercials, fewer uses of the phrase “man cave.” Yet the shift in the gendering of DIY also confirms Gelber’s argument that “doing-it-yourself” was a form of productive leisure that also reproduces gender roles in the home. Search Twitter for “DIY” and you will find women’s magazines offering plans for DIY jewelry, Martha Stewart’s DIY pumpkin spice latte, even something called a “DIY chicken coop chandelier.” Much of this usage, which seems to want the anti-establishment posture of Whole Earth or Kill Rock Stars, drains the phrase of the particular meanings it once had (there’s no solidarity in a pumpkin space latte) or even any meaning at all (didn’t “DIY dinner” used to be called “cooking”?).

And then there is this: “Drone it yourself,” a military-style drone you can assemble and launch all by yourself.