The latest in an irregular series, in which two–or, in this case, three-similar words enter, and only one–or, in this case, two–leave.

The primary season has reintroduced us to “the “establishment,” a concept just as often ironically capitalized as “the Establishment.” But how is “establishment” different from the two other most popular shorthand names for the structures that order our lives: “the system” and the most figurative one, “the Man”?

“The man” is hardest to trace, since the African American vernacular phrase vanishes into the databases that capture any use of the word “man” and the definite article. Slang dictionaries date it to the 1940s, where it referred to “the white ruling class.” In some of his work, James Baldwin emphasized that the man was embodied by the cop but he resided, as well, at work: “And the others, who have avoided all of these deaths”—from heroin, exhaustion, Korea, or the police—“get up in the morning and go downtown to meet ‘the man,’ he wrote in “Fifth Avenue, Uptown.” In his harrowing short story “Going to Meet the Man,” which is told from the point-of-view of a southern policeman, Baldwin emphasized what a poisonous mixture of of sexual repression and self-loathing there is in “the man” himself. But the man, like “establishment,” has suffered a sort of sneering fate recently—“sticking it to the man” is how some ironic office worker might now describe refusing to clean the microwave in the office break room.

“The man,” like “establishment,” summons the 1960s and 70s, the high-water marks for each. Mark Leibovitch takes on “establishment” in the latest edition of the New York Times Magazine’s “First Words” column, a series of essays on the politics of popular language about which this blog has struggled to maintain a polite silence so far. His column is an anecdotal account of establishment’s popularity in the 2016 presidential campaign, but his tone of raised-eyebrow bemusement at the proliferation of the “Establishment” is also a good example of the term’s historic uses. That is, the word has been used by members of some establishment to describe its challengers or critics just often as it has been used by those very critics. Leibovitch writes:

The establishment represents a catchall designation for ‘people in charge’ — and implies that they’ve been ensconced too long. The establishment is tired and musty and too comfortable. Yet it is still invoked constantly as a phantom solution: The establishment will step in and bring order to this chaos. They are the parents that will arrive home just as the party has grown out of control, the house is being trashed and the cops are taking names.

His metaphor of angry parents gets at something important. “Establishment” is used less often by radicals and activists than by members of the establishment who condescending to them or trying to co-opt them. The Establishment is orderly, rational, reasonable; the anti-Establishment is churlish, irrational, led around by its teenage passions. These anti-Establishment radicals, of course, are usually young, and given the role of so-called “millennials” in the Democratic primary, this explains a lot about the word’s resurgence.

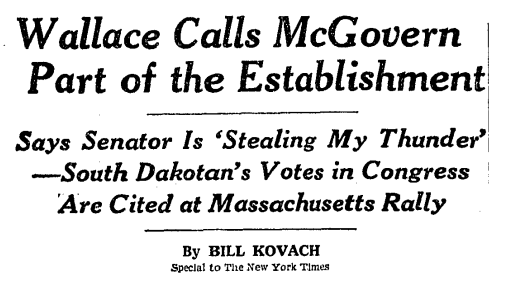

George Wallace, in his Trump–like 1972 presidential campaign, liked to style himself as the anti-establishment candidate, accusing George McGovern of “stealing his thunder” in that respect.  Abbie Hoffman, who embodied the white “anti-Establishment,” was brought up in an improvised court of his peers for plagiarism, which to a reporter in 1971 was just the most delicious contradiction. (But aren’t courts…the Establishment?!? Game, set, match, Yippies.) Charles Manson “preached a mixture of love for fellow men and hatred of the establishment to his devoted followers,” wrote the Times after his arrest. And Jimmy Hoffa, according to an unsympathetic 1967 profile, “played to the hilt the fiction that he was the persecuted Everyman, the scapegoat of the Establishment.” In none of these examples does “the Establishment” actually exist—it’s a fiction that ideologues concoct to deceive the gullible.

Abbie Hoffman, who embodied the white “anti-Establishment,” was brought up in an improvised court of his peers for plagiarism, which to a reporter in 1971 was just the most delicious contradiction. (But aren’t courts…the Establishment?!? Game, set, match, Yippies.) Charles Manson “preached a mixture of love for fellow men and hatred of the establishment to his devoted followers,” wrote the Times after his arrest. And Jimmy Hoffa, according to an unsympathetic 1967 profile, “played to the hilt the fiction that he was the persecuted Everyman, the scapegoat of the Establishment.” In none of these examples does “the Establishment” actually exist—it’s a fiction that ideologues concoct to deceive the gullible.

In the summer of 1968, Time magazine wrote:

The anti-establishment forces at work in the U.S. today-black militancy, the poor people’s crusade, the antiwar movement, student riots and demonstrations over these and other issues-are comparable in causation if not degree to the upheaval in France. In both countries, and many others, the malaise reflects the resentment of those who feel that they have been neglected, ignored or oppressed by outdated, inflexible political and bureaucratic systems.

I doubt you could have found many Black Panthers who would have complained about their neglect by the state—they would have welcomed a little more police neglect, as opposed to the alternative. This is a common liberal response to moments of political dissent, echoes of which resound in the campaign media today. Look at Paul Krugman, who calls Bernie Sanders a “demagogue,” not because he is mobilizing a mob, as the OED would require, but because to him, all militancy is “the mob.” (Whether or not Sanders is militant is another question; the point is that Krugman thinks he is).

“Anti-establishment” politics is all personal, that is, as motivated not by coherent grievances but by feelings that are only skin deep–anger, “malaise,” as Time said, or a loyalty to a leader. This reading of the radical as irrational is extended most of the time to people of color, the post-colonial world, especially Latin America. It also extends to young people in general, to feminists, and only occasionally to supporters of white men like Sanders and Trump.

“System,” by contrast, is usually spoken in earnest. It has more in common with “power structure,” the term that along with C. Wright Mills’ “power elite” seemed to be more popular than “establishment” by intellectuals on the left in the 60s. “Systems” name particular institutional locations of oppressive authority—the criminal justice system, the banking system, or the interlocking network of all of these–“the system.” By its nature, a “system” is oppressive, since we tend to think that system constrain rather than facilitate freedom. A system is less amorphous than “the establishment”; it can be named and opposed more clearly.

As Leibovitch says, “the establishment makes for a potent straw man in the hands of people who otherwise might not know precisely what they’re fighting, only that they’re angry and frustrated.” The establishment is certainly a political straw man, now as ever, attacked opportunistically and selectively. But so is “the Establishment”–the concept itself. In its historic and current usages, there is either a) no such thing as the Establishment b) there is such a thing, but it’s not so bad, it basically just means you’re white and from New England, and/or c) there is an Establishment, and it’s opposed by impassioned, malaise-y young people. Whatever it is, you can’t beat the Establishment, you can only join it. Where’s my column, New York Times Magazine?

Winner: The Man and The System, in a tag-team KO.

Abbie Hoffman, who embodied the white “anti-Establishment,” was brought up in an improvised court of his peers for plagiarism, which to a reporter in 1971 was just the most delicious contradiction. (But aren’t courts…the Establishment?!? Game, set, match, Yippies.) Charles Manson “preached a mixture of love for fellow men and hatred of the establishment to his devoted followers,” wrote the Times after his arrest. And Jimmy Hoffa, according to an unsympathetic 1967 profile, “played to the hilt the fiction that he was the persecuted Everyman, the scapegoat of the Establishment.” In none of these examples does “the Establishment” actually exist—it’s a fiction that ideologues concoct to deceive the gullible.

Abbie Hoffman, who embodied the white “anti-Establishment,” was brought up in an improvised court of his peers for plagiarism, which to a reporter in 1971 was just the most delicious contradiction. (But aren’t courts…the Establishment?!? Game, set, match, Yippies.) Charles Manson “preached a mixture of love for fellow men and hatred of the establishment to his devoted followers,” wrote the Times after his arrest. And Jimmy Hoffa, according to an unsympathetic 1967 profile, “played to the hilt the fiction that he was the persecuted Everyman, the scapegoat of the Establishment.” In none of these examples does “the Establishment” actually exist—it’s a fiction that ideologues concoct to deceive the gullible.